America’s first Air Mail Mechanics and The Mechanical Laboratory

I was certain this was the finish. On the way down I had expected to get it, but I didn’t care so much for myself as I did for Radel, the mechanic. He was strapped in there helpless, depending on me and I had failed him. Air Mail Pilot, Eddie Gardner, 1918 After both he and his mechanic survived a crash.

In 1918, while he was a Captain in the Army Signal Corp, Benjamin B. Lipsner (1887-1971) was placed in charge of operations and maintenance for the newly formed U.S. Air Mail Service. Lipsner knew that he was contributing more to aviation history than supervising the safety of his pilots. These first pilots and mechanics created the unchartered air routes between eastern cities, and this led to the transcontinental airway system.

“The air mail route is the first step toward the universal commercial use of the aeroplane,” said Lipsner. “The air mail service is the mechanical laboratory for the advancement of commercial aviation.”

There are volumes written about the original military pilots (May to August, 1918) and their civilian successors (1918-1924), but less is documented about the mechanics whose intelligence, courage and skills kept the biplanes flying. Photos of men in greasy coveralls in front of a hangar are often labeled only “AMS mechanics.”

At the onset of WWI, the U.S. Air Service trained more than 10,000 mechanics. Of these, some of the best were plucked from overseas assignments to work on the newly formed Air Mail Service’s Curtiss JN4 (“Jennys”) and reporting to Capt. Lipsner.

Lipsner’s “Boys”

Lipsner was born in Chicago and his curiosity for all things mechanical began as a child, growing stronger with his progression through high school and college. By 1910, at age 23, Lipsner worked as a mechanic in an automobile factory, soon leaving the assembly line floor to specialize in management of personnel and manufacturing operations. By all accounts he was a personable man, genuinely interested in the well-being of the mechanics he supervised. The “air-age” captured Lipsner’s attention, but he was less interested in flying an aeroplane than he was in their power plants. He joined the Air Signal Corp when the U.S. entered WWI, serving in maintenance of aircraft. Before the war ended, President Wilson pressed congress to release funding for the creation of the U.S. Air Mail Service and chose Lipsner as head of operations. Lipsner hired pilots, set up landing fields, arranged scheduling, and made sure maintenance of aircraft was a priority. He has been described as protective of his “boys” on the job, and rarely put a deadline before safety.

When USPO’s successful military program was transferred to civilian employees, President Wilson asked Lipsner to resign his commission so that he could head the new U.S. Aerial Mail Service. Lipsner’s seven original aerial mail pilots were: C.D. DeHart, Ed. V. Gardner, Louis Gertson, Max Miller, Maurice A. Newton, Robert Shank and R. Smith. Lipsner’s pilot’s were required, among other assets, to have at least 1,000 hours of flying time.

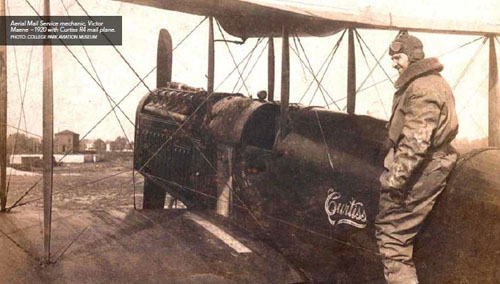

The eight original aerial mail mechanics were E.N. Angle, W.O. Beatty, A.F. Cryder, J.A. Danville, Charles King, Edward C. Radel, William C. Read and Henry Wacker. Other mechanics, like Victor Maene and R. Heck, are mentioned in connection with the 1918 crew, and were likely part of the following civilian takeover.

Cigars in the Fog

Although classified as ground crew, mechanics frequently accompanied the mail. Strapped in, but without any controls to use in case of a pilot emergency, they were basically cargo — although the pilots certainly regarded them as valuable teammates, if not friends.

My research uncovered Cryder referenced in 1919 and again in 1929 related to work in aviation, as well as a sad report about Waker and another mechanic, Carl “Buck”Weaver. In 1919, they survived a fiery crash with 13 fatalities, while in a lighter-than-air ship. Waker dropped entirely out of aviation until the onset of WWII when he went to work inspecting aircraft for Bell. He lived to be 82. Lipsner chose Radel as chief mechanic to service the original Jennys, and later the DH4 (deHavilland) and Curtiss R4s. On Sept.10, 1918, Gardner took Radel with him on a flight between Chicago and New York. They took off in a rain storm and arrived in Cleveland where they had to wait for fuel which delayed their schedule so that Gardner was forced to fly part of the way at night. The trip was at first uneventful, even beautiful, as Gardner later described his first views of the sparkling city lights below him. Running out of fuel, and just 10 miles short of their Long Island destination, Gardner made a forced and near-deadly landing. He once described the experience as the most harrowing half hour of his life. “I was dead,” Gardner later sheepishly explained to Lipsner. “There was no doubt about it. It wasn’t so bad now that I look back on it. But I might have known I’d have to come back and face the music for what I’d done to Radel.” Neither Gardner nor Radel were seriously injured and they were the first to fly between the two cities in less than 24 hours.

Gardner and Radel’s close call was not unusual, and it is remarkable that none of the military original pilots and mechanics were badly hurt or killed.

USPO civilian pilot James Hill would light a cigar when he left Ohio. When the cigar ashes burned his fingers he knew he had reached his first refueling destination in Pennsylvania. Hill died while transporting mail at the age of 36. Aviator E. Hamilton Lee was one of the first USPO civilian pilots, and survived when 34 of his fellow pilots and mechanics did not. “We had no parachutes, no radios, and few instruments,” he wrote. “We flew mostly by landmarks — when we could see them. In fog or thick clouds we just flew by the seat of our pants.” Lee lived to be 103.

Lipsner’s management style was hands on, nevertheless he reported to USPO Postmaster General Albert Burleson and Assistant Postmaster General Otto Praeger, who did not always agree with his decisions. In May 1918, Katherine Stinson had been exhibition flying for six years and then owned a Jenny. She received a one-time position as clerk of the Chicago post office and delivered 61 letters to New York, but not without three accidents en route. She then made one air mail delivery within Canada, and returned to the U.S. Soon thereafter, she reportedly went to Lipsner’s Washington office and asked for a job flying the mail, but he turned her down. Burleson reversed the decision and Lipsner hired her. That September, Stinson flew one round-trip between Washington, D.C., and New York, successfully delivering 150 pounds of mail. For reasons still unknown, she quit her Aerial Mail Service job after this one flight, and was soon a volunteer ambulance driver for the war effort in Europe.

The discord between Lipsner and Praeger escalated quickly over matters of funding for aircraft and hiring of pilots, and after his brief but significant term, Lipsner resigned. Before he left, among other contributions, Lipsner sought safer aircraft which could fly farther, faster and carry a heavier payload. To that end he purchased new Standard Aircraft Corporation JR-1Bs to replace the aging Jennys, and later referred to this change as the “true beginning of the air mail.”

Lipsner went on to work as an independent consultant for oil companies and airlines. He was also a popular public speaker, and at banquets in his honor he often regaled his colorful days with the USPO — when pilots flew through fog “by the seat of their pants.”

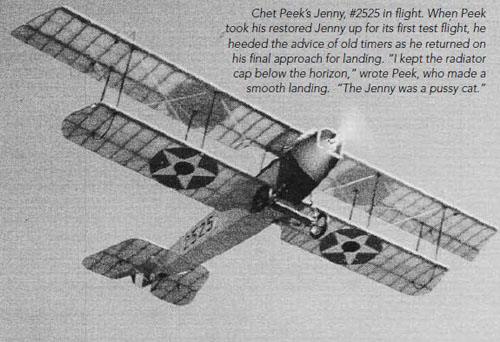

Among the aircraft which made our first U.S. air mail possible are the deHavilland DH4, the Curtiss R4 and the Curtiss JN4, known affectionately as the “Jenny.” The WWI surplus Jenny came to symbolize barnstorming, as did the Lincoln Standard, but it was the Jenny which was selected to appear on the first air mail stamps and thereafter became recognizable to the general public. In 1921, Amelia Earhart learned to fly in a Canuck, the Canadian version of the Jenny, and about the same time, Charles Lindbergh kept his Jenny airworthy during his barnstorming days before signing on as an air mail pilot. It was restored and is now on display at the Cradle of Aviation Museum on Long Island, NY.

I now know several mechanics who have either fully restored a Jenny or worked on one. Chet Peek of Oklahoma completed the restoration of a Jenny found in an Iowa barn during 1970. From 1983 to 1987, Peek rebuilt the wreck into an airworthy beauty which has been displayed at the EAA Museum at Oshkosh, WI, since 1990. I’ve just become acquainted with Brian Karli of Georgia, who began his ongoing restoration of a Jenny in 2006.

Peek and Karli have both documented every nut and bolt, and every piece of fabric and wood of their Jennys. The details are found in Peek’s book, “The Resurrection of a Jenny,.” (More information on Peek’s book can be found at www.threepeakspub.com, and Karli’s blog can be found at www.curtissjennyrestoration.blogspot.com

Don’t blame me if you become obsessed with finding your own Jenny in a barn.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.