Charles E. Taylor

May 24 is now a date celebrated across the United States as “Aviation Maintenance Technician Day” because it was that date in 1868 that Charles Edward Taylor was born. Taylor’s story began in a log cabin on a hog farm in Illinois.

Disinclined to be a farmer, Taylor finished high school in Lincoln, NE, already employed alongside grown men in what was to become his first job in a lifetime of work. Taylor’s unusual and close relationship with both Orville and Wilbur Wright as an employee was intermittent for decades due to the early years when the aviation industry was finding its niche as a modern marvel. Taylor worked for several years with “the boys” and had his first ride as a passenger with Orville in 1910. The Wrights did not encouraged him to take flying lessons, perhaps because they didn’t want to lose their mechanic to exhibition flying at air meets and county fairs. Although he could have earned a huge income, Taylor may have lived longer by not taking to the air. Many exhibition fliers were killed before WWI, including several who worked for the Wrights.

Working for “the boys”

Taylor understood nearly anything mechanical. He found work in both Nebraska and California before he settled down in the 1890s with his bride, Henrietta, whose family knew the Wrights in Dayton, Ohio. He worked as a machinist in Lincoln and eventually moved to Dayton. By 1901, Orville and Wilbur determined they needed to hire someone who could take over their bicycle shop while they made flight tests at Kitty Hawk, S.C., and Taylor was, as one historian worded it, “someone they could trust.”

As the Wright’s “foreman machinist,” Taylor was immediately immersed in the brothers’ trial-and-error process to construct a wood-and-fabric flying machine. Satisfied with their gliding experiments by 1903, the Wrights next required an engine for powered flight. They were unable to find a power plant that was light enough and powerful enough to lift both man and machine — which by this time had a wing span of 40 feet. The boys knew what they needed and assigned this challenging task to Taylor. All three sketched parts on scraps of paper, but, as Taylor later recalled, “We didn’t make any drawings.” Using the bicycle shop’s lathe, drill press, grinder and hand tools, he built an efficient 12hp engine that weighed 180 pounds. It took him only six weeks. The block with which Taylor worked was aluminum, and other parts (magneto, valves, rubber hose) were purchased. The Wrights’ biographer, Tom Crouch, put it succinctly when he said, “Taylor made do with what he had.”

While Orville and Wilbur made the world’s first powered, manned aeroplane flights at Kitty Hawk that December, Taylor kept their shop open for business. By 1904, Orville and Wilbur set up a flying field to test their aircraft. The field was known as Huffman Prairie and was located on a meadow near Dayton, next to the railroad stop at Simms Station. There they built a shed and a catapult from which to launch their ships. Taylor’s new responsibility was to manage the flying field.

For the next five years and with Taylor’s help, the Wrights improved their aircraft and engine designs. The Taylors were not socially close to the Wright family but Charles gained the nickname of the “other Wright brother, due to his contributions toward their inventions. He worked side by side with the brothers on their 1905 model (now with a heavier and more powerful engine) and later with them on an unsuccessful attempt to adapt their aircraft to a hydro-aeroplane in 1907.

Demonstration flights

Taylor’s world expanded when the Wrights decided to demonstrate their aeroplane in European countries, hoping for foreign sales. At this time, many people who had not actually witnessed an aeroplane in flight remained skeptical of the claims that any aircraft could maneuver turns and fly at varied altitudes. Wilbur’s public flights in France created a sensation. The Wright brothers were soon among the most famous people in the world at the time.

During September, Orville and Taylor were at Fort Meyer, VA, to make a demonstration flight for Army officials who considered purchasing the aeroplane for observation purposes. According to some sources, this was to be the day that Orville promised Taylor his first ride as his passenger. Reportedly, Orville was urged to take Lt. Thomas Selfridge instead. Orville was known to be an excellent aviator, but he could not control his aircraft when one of the propellers disintegrated. The resultant crash killed Lt. Selfridge and injured Orville severely. Taylor was first on the scene to help remove their motionless bodies. Orville survived but suffered from the emotional and physical toll the rest of his life.

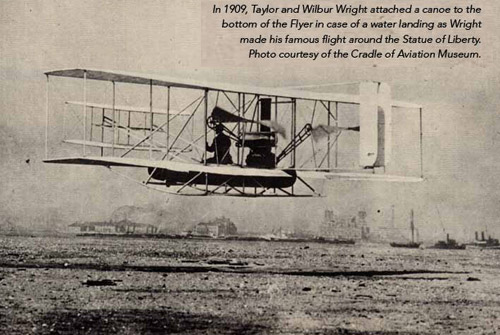

In 1909, while Orville was recovering, Taylor joined Wilbur in France for further flights. They both returned to the U.S. as Wilbur performed one of the most memorable and dramatic moments in aviation history. Heretofore flights over cities and water were considered dangerous due to the variations in air currents. For the 1909 Hudson-Fulton anniversary celebration in New York City, both Wilbur and Glenn H. Curtiss agreed to make flights over the Hudson River up to Grant’s Tomb, leaving from Governor’s Island. Newspapers reported temporary tent hangars for both Wilbur and Curtiss were built side by side on Governor’s Island — close enough for casual conversation between the two men who had become rivals. Historians agree that Curtiss did not make the flight, but Wilbur thrilled hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers by flying his aircraft (with a canoe tethered beneath) over the Hudson and around the Statue of Liberty.

Progress and prizes

The year 1909 was a big one for the boys, made more significant due to the incorporation of the Wright Company, with a factory in Dayton. The entire machine, except the engine, was constructed at the plant while Taylor continued to build all the engines at the bicycle shop. The test flights were made on Huffman Prairie when assembly of a new aircraft was complete. It was at Huffman Prairie that Orville finally took Taylor up for his first flight in 1910.

During this time, European aviators competed in air meets with American fliers. Grand prizes such as the Gordon Bennett Trophy for speed and the Wannamaker trophy for altitude attracted aviators in Bleriots, Antoinettes, Farmans and other variations of monoplane and biplane designs, as well as aircraft by Wright and Curtiss. Millionaire Randolph Hearst offered $50,000 for the first successful flight across the U.S. made within a 30-day period. Aviator Calbraith “Cal” Rogers set out to win the prize, flying a Wright machine named the “Vin Fiz” for the soft drink company that sponsored his attempt. Taylor left the Wrights and hired on as Rogers’ mechanic, with pre-trip work in California. In September 1911, Rogers took off from New York with Taylor and others following in a “Vin Fiz” train to meet him where he either crashed or planned a maintenance stop. Rogers finished the flight at his destination in southern California but did not meet the time frame to win the prize. He died in an accident shortly thereafter. Back in California with his young family, Taylor found work with dirigible and balloon designer A. Roy Knabenshue of Pasadena. He also worked for Glenn Martin who flew from a field at Griffith Park in Los Angeles.

A Life’s Landing

During 1912, many major events changed Taylor’s life forever. Wilbur became ill and died. Taylor moved his family back to Dayton and the Wright Company rehired him to test engines. Henrietta became ill and was hospitalized and their infant daughter was sent to live with relatives. Henrietta never recovered and died several years later in Dayton.

Taylor left the Wright Company and accepted subsequent jobs in several different states. He returned to Dayton as an employee for the newly formed Dayton Wright Company in 1916 and later for the Martin-Wright Aircraft Company. After Martin-Wright closed in 1919, Taylor found more steady work with the reorganized Dayton Wright Company after working a short time in Orville’s Dayton “Aeronautical Laboratory.”

Taylor, now nearly forgotten despite his association with the famous Wrights, worked at several jobs in California between 1926 and 1936. Although advanced in age, he was not financially secure enough to retire. Henry Ford pulled him back into the limelight by hiring him to help recreate the Wrights’ bicycle shop and home, and to build a scaled-down replica of his 1903 engine for a museum at Greenfield Village, Dearborn, MI. At age 70, Taylor was there for the museum dedication, but soon left Dearborn and moved back to California.

Taylor continued to work until 1944, when he retired due to health problems. In 1948, Orville died, leaving an annuity of $800 per month for Taylor. By then, Taylor desperately needed the funds. Learning of his financial difficulties, the Aviation Industries Association began supporting him until his death in southern California in 1956 at the age of 88. Both Taylor and Orville died on January 30.

Taylor was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1965. All those who rest beside Taylor’s grave at the Portal of the Folded Wings followed due to his efforts as the Wright brothers’ mechanic.

Soon after the Wrights made their first flying exhibitions in Europe, a slogan that may best describe the “third Wright brother” emerged:

“The Wright brothers made the glider, but Charles Taylor made the glider an aeroplane.”

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.