Layers of wood and insanity - One Tree Flying

Harry N. Atwood [1884-1967] learned to fly at the Wright school in Dayton, Ohio, in May 1911. In just two weeks, he mastered the complicated control system of the Wright biplane and made headlines as the “serious” flier who represented the future of aviation. Atwood’s fame grew after landing his biplane on the White House lawn, greeted by President Taft who presented him with a gold medal. As much as he loved to fly, Atwood’s brief and unfinished education at MIT infused him with a greater passion for invention. As quickly as he came on the scene, Atwood disappeared to live a secluded life in New Hampshire. He publicly reappeared in 1935 with a monoplane constructed of “duply,” a wood-laminating process he created after working in a furniture business and a chemical company. At the time, veneer was not a new concept to aircraft design, but the materials and process were never optimally developed — except in the mind of Harry Atwood.

The Early Bird society of pioneer aviators excitedly announced Atwood’s invention in their newsletter, Chirp. Their report crowed that Atwood built his entire aircraft using his “specially-processed veneer” from “one birch tree, six inches in diameter.” Helping him to finish construction and make the first test flight was famed cross-Atlantic flier Clarence Chamberlin. The low-wing monoplane, known only as “Atwood’s duply aircraft” was reportedly powered with a 30 hp engine that could fly 120 mph. With a wing span of 25 feet, the sturdy aircraft was assembled in sections.

“His goal,” reported Chirp, “is a one-piece plane, built entirely of laminated wood. He produced an experimental rowboat, skis, toilet seats, heels for ladies’ shoes, and a variety of molded forms. But his dream as a flyer was to perfect a plastic airplane.” The duply process involved using a wooden form over which was placed a layer of cellophane and then covered in Atwood’s thermo-plaster.

“Strips of veneer, 20-thousandths of an inch thick, are wound around the form,” reported Chirp. “Then comes a coating of rubber insulation. The entire form is wheeled into a steam room and cooked for three-quarters of an hour. After the cooking, the rubber insulation and form are removed, leaving the veneer baked hard in the desired shape.”

A reporter from the Nashua Telegraph described Atwood as a “genius — brilliant, and certainly ahead of his time. He had developed a forerunner of modern plastics.” On June 13, 1935, Chamberlain made a successful test flight at Nashua, N.H., and Atwood’s hopes for future sales soared. Chet Peek had built several small aircraft and believes Atwood’s idea was sound, if not advanced. He speculated that Atwood’s finished product was “a bit heavier than they anticipated,” which might have accounted for the lack of manufacturers interest .

Atwood lived a long, if unconventional life. In the decades before his death at age 83, he had abandoned further development of “duply” while residing in the woods of North Carolina, isolated from his family and friends, and obsessed with the use of concrete.

A few years later, veneer aircraft construction was poised for a giant comeback.

The Flying Lumberyard

The Hughes H-4 Hercules (“Spruce Goose”) was originally a joint design between ship builder Henry J. Kaiser and aircraft designer Howard Hughes [1905-1976], during WWII. Kaiser opted out, leaving the military-contracted project entirely to Hughes.

In order to transport cargo and personnel across the Atlantic during WWII, Hughes (and his employee, Glenn Odekirk) designed the largest aircraft ever built at the time, restricted by the lack of metal — in particular, aluminum. Using birch (not spruce), Hughes’ enormous flying boat was made of laminated wood. It is technically described as a “form of composite technology” — using plywood and resin (the “Duramold process”). Critics of the aircraft dubbed it the “flying lumberyard.”

With a wingspan of 319 feet, the Hercules could fill up a football field. At 80 feet high, its enormous interior was designed to carry 400,000 pounds. It was powered by eight P&W R-4360 Wasp engines (4,000 hp), each with a four-bladed, 17-foot Hamilton Standard propeller. The Hercules was perfected to reach 21,000 feet, cruise at 250 mph, and go without fuel for 3,000 miles.

Construction of the Hercules dragged on past the end of the war, delayed in part due to the eccentric and exacting demands of perfection Hughes imposed. Built in Long Beach, Cal., the Hercules remained in a secret hangar until Congress required Hughes to account for his use of government funding. On Nov. 2, 1947, with Hughes at the controls, the Hercules flew low over the ocean and remained gracefully airborne for about a mile. By the time of its successful debut, the Hercules was obsolete and never flew again.

Useful inventions and powerful business connections made Hughes a wealthy man, but his eccentricities developed into obsessive-compulsive disorders and, like Atwood, he died reclusive and disconnected from family and friends in 1976. He was 71 years old.

Out of sync with their industry, Atwood and Hughes both designed aircraft that never went into production. However, a veneer-constructed aircraft designed by a more conventional predecessor enjoyed great success.

A True Spruce

During the 1920s, aircraft manufacturers like the Loughhead brothers (later, Lockheed) built aircraft for the “common man.” Their designer, Jack Northrop [1895-1981], was typical of early fliers that hesitated to morph from wood and fabric directly to all-metal aircraft. Instead, he invented a sport plane called the S-1. It was made of plywood and led to the famous Lockheed Vega.

In an article written by engineering professor and editor Stephen J. Mraz, the history of aircraft constructed of plywood includes the development of the Vega:

“Northrop came up with a novel way to make the monocoque fuselage for the S-1. Technicians placed three layers of spruce plywood strips saturated with casein glue in the bottom half of a 21-foot-long concrete mold. They put an inflatable rubber bag on top of the material, then bolted on the top half of the mold. The bag was inflated, uniformly pressing the plywood into accepting the shape of the mold, and pressure was maintained for 24 hours. The resulting quarter-inch-thick half shells were joined with glue and formers, making a smooth, bullet-like fuselage.

Northrop and Gerard Vultee then built the Lockheed Vega, using the same half-fuselage construction method used for the S-1. This time, they added stringers, making the four-passenger aircraft a semi-monocoque design. It also had a wood-skinned wing.”

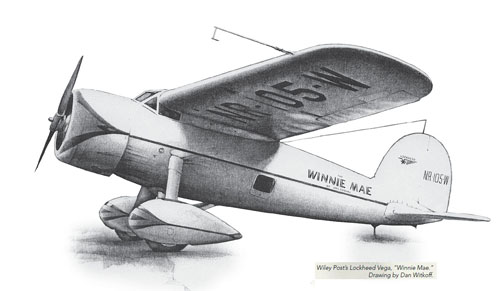

The Vega was introduced in 1927, with a top speed of 135 mph using a 225 hp Wright Whirlwind engine. Within two years it was adapted for racing and set altitude and transcontinental speed records when flown by famous aviators, including Wiley Post, Amelia Earhart and Rosco Turner. As for Northrop, he soon started his own company, becoming a passionate advocate for the “flying wing” aircraft design and died in1981 at the age of 86.

Reviewing successes like the Vega, Mraz concluded, “Technologists and futurists assure us composites will dominate the industry — but no one can point to solid evidence that composites are any better than metal, or wood and fabric, for that matter. They might be stronger or lighter, but they’re more expensive to make, more difficult to inspect, and trickier to repair.”

Corporate research projects now dominate the advancements in aircraft design, but there was a time when aviation depended upon the contributions of eccentric, brilliant, daring and colorful individuals. Like plywood veneer, these remarkable (if sometimes imperfect) people created the layers of history which gave strength to American aviation.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects at www.harrietquimby.org.