Masterful Willa Brown (1906-1992)

From photographs alone, we can see that Willa Beatrice Brown (Chappell) was beautiful, daring and a trifle flamboyant. Beyond her broad smile and beneath her fashionable white jodhpur flying costume was an academic with a rare talent for business administration. She was also fearless on many levels while racial segregation permeated public schools and the military.

She was born in Kentucky in 1906, and while in grammar school her family moved to Chicago. During these years of prohibition and gang wars, Brown’s father was a minister and provided a stable home in which she had financial support and family encouragement for her to learn, and then apply, the skills which made her so unique. Nevertheless, she contributed to her own success by working while gaining an education.

Brown graduated from high school in Terre Haute, Ind., in 1923, received a bachelor’s degree in business from Indiana State Teachers College in 1927 and went on to earn her Masters in business administration from Northwestern University in 1934. While many in the nation were jobless, if not homeless, Brown reportedly could type and take shorthand as well as she could manage a profit and loss statement. Between 1927 and 1939 she often found government jobs, including employment as a public school teacher, social service worker, as a clerk in the post office and for the Works Public Administration (WPA). She also found work elsewhere as a cashier at a drug store and as a secretary and laboratory assistant for offices in colleges and doctor’s offices. Sometime during those busy years emblemized by Bessie Coleman, Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart, the lure of aviation drew her in. She took flying lessons from Dorothy Darby and Col. John Robinson, two black fliers who were well known in the Chicago area during the 1930s. Darby was a graduate of Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical University (CWAU) in Chicago and an exhibition parachute jumper. Robinson was a pioneer advocate for schools and organizations promoting involvement of blacks in aviation.

The Master Mechanic

It seems Brown never did anything without becoming a “master,” and that included her quick and yet determined study of aircraft maintenance. She was one of very few women at CWAU, yet she excelled and earned her aircraft mechanic’s license in 1935.

In 1938 she gained her private pilot’s license after taking advanced flying lessons at Harlem Airport from Cornelius R. Coffey, who she knew through the Challenger Airmen’s Association (CAA). Fred and Bill Schumacher owned the Harlem Airport outside Chicago, where they ran a flying school for white students at one end of the airport and leased Coffey the space at the opposite end. Having been divorced following a brief marriage, Brown fell in love with Coffey and they lived together at the airport. They were a good team and soon offered both academic and practical education at the Coffey School of Aeronautics where they imposed no restrictions on gender or race. Brown was the school’s Director from 1940 to 1941 and there is no doubt that her business administration skills kept the doors open.

Coffey remained the primary flight instructor and Brown taught aircraft mechanic classes in Chicago. Nevertheless, Brown became an excellent pilot and instructor, and taught students in the school’s J3 Cub. If a student was having difficulties, Brown was known to spend extra free time giving private lessons. No student strapped for funds went without a meal. They could count on “incidentals” often supplied by Brown and Coffey. Some of their young students went on to become members of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, otherwise known as the Tuskegee Airmen, during WWII.

During the pre-WWII years, Brown and Coffey began their life-long advocacy, if not profession, toward integrating nationally-funded aviation programs to include schools owned and operated by blacks, with the ultimate goal of racially integrating the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) and the U.S. Air Force. In their quest to change a decades-old system, Coffey, Brown and their contemporaries must have encountered several challenging barriers that they overcame — if history records it properly — with grace and safety. Brown appears to have moved forward seamlessly without causing major conflicts. After a brief marriage with no children, Brown and Coffey divorced.

During the pre-WWII years, Brown and Coffey began their life-long advocacy, if not profession, toward integrating nationally-funded aviation programs to include schools owned and operated by blacks, with the ultimate goal of racially integrating the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) and the U.S. Air Force. In their quest to change a decades-old system, Coffey, Brown and their contemporaries must have encountered several challenging barriers that they overcame — if history records it properly — with grace and safety. Brown appears to have moved forward seamlessly without causing major conflicts. After a brief marriage with no children, Brown and Coffey divorced.

Brown’s list of firsts will probably never be fully known, as she was going where no other black woman had previously gone. To be sure, her most famous “firsts” are;

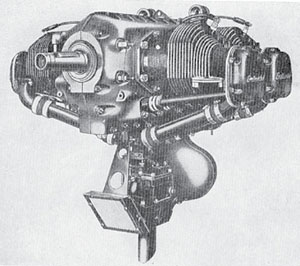

• Member and chairperson of the education committee for the Challenger Air Pilots Association, one of the first black pilot’s organizations in the USA (1931), so named due to the Curtiss Challenger engine;

• Founder, with Coffey and Enoc P. Waters, of the National Airmen’s Association of America (1939), becoming their first national secretary;

• Founder, with Coffey, the Coffey School of Aeronautics (1940);

• First black (male or female) officer in the Civil Air Patrol (1942);

• First and only U.S. woman (of any race) to be certified as an A&P and as a commercial pilot (1943);

• First black woman to run for a Congressional seat (1946, 1948 and 1950, unsuccessfully in Illinois)

It is difficult to know when Brown had time for much other than aviation after WWII when she appointed herself a traveling advocate for the integration of aviation programs. Giving exhibition flights and making public appearances, Brown was an attractive and eloquent representative of the future for equality in the air. One of Brown’s biographers deduced that Brown’s effectiveness was because she was widely respected in the white male-dominated field of aviation, gaining support for her causes. She was well educated with years of practical experience. She was courageous but not reckless. She was passionate but not unreasonable. For all these attributes and more, Brown is considered a major character in the eventual integration of the U.S. military by Order of President Harry Truman in 1948.

Brown became Willa Chappell in 1955, her third husband being a minister like her father. Having no children of her own, she made her students her extended family and established children’s flight clubs. She continued to teach and finally retired from the public school system in 1971. She was appointed to the FAA Women’s Advisory Board in 1972 and remained active in several national aviation organizations. She died of a stroke in 1992, at age 86.

Brown became Willa Chappell in 1955, her third husband being a minister like her father. Having no children of her own, she made her students her extended family and established children’s flight clubs. She continued to teach and finally retired from the public school system in 1971. She was appointed to the FAA Women’s Advisory Board in 1972 and remained active in several national aviation organizations. She died of a stroke in 1992, at age 86.

The Queen and The Dean of “Black Wings”

Bessie Coleman, sometimes known as “Queen Bess,” was the first black American woman to earn her pilot’s license – but not in the U.S. Turned down by American schools of flying, Coleman earned her license in France during the 1920s and returned to make exhibition flights in her native country. Dissimilar in lifestyle, these two women were alike only in their passion for flying, which ended in a fatal accident for Coleman in 1926. Coffey and Brown initiated an annual fly-over of Coleman’s grave at Lincoln cemetery in Chicago with a low-pass flower drop. After her death, Brown was added to Chicago’s list of “Aviation’s Pioneer Colorful Women” and flowers were dropped from aircraft over her grave as well. The Willa Brown Scholarship Program was made available for girls studying aviation at Buena Vista High School in California during 2000, which would no doubt have pleased the teacher of so many potential aircraft mechanics and pilots.

Brown was inducted into the Kentucky Aviation Hall of Fame in 2003.

Correction: In the Bench Marks article in the Nov/Dec issue of D.O.M., the last paragraph on page 11 states, “On Jan. 18, 1911, Ely made a round trip from a field by San Francisco Bay to Pennsylvania with his Curtiss biplane.” It should have read that he made the round trip “to the cruiser Pennsylvania…” ed.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects on her web site: www.harrietquimby.org.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian, magazine columnist and author. In 2008, she was awarded the National DAR History Medal and has appeared in documentaries on PBS and The History Channel. Learn more about her aviation history projects on her web site: www.harrietquimby.org.