PDCA - Plan | Do | Check | Act

My last article, “The Red Queen,” led you into the Plan, Do, Check and Act (PDCA) cycle and discussed the planning portion. PDCA is a continuous improvement cycle that was popularized by W. Edwards Deming, the quality guru who went to Japan after WWII ... and the rest is a painful history lesson for America. Now for the rest of the story.

The “DO” part

You did your planning, now just do it! There is a little more to it than just that. Consultants are notorious for showing how to do something, collecting their money and departing before you have to implement what was suggested. The “Do” part is the dirty part because it is the hard part. This is the point where many organizations just give up in frustration.

First off, no plan is perfect. In fact, perfection is a fallacy as well as a subject for another article. I can’t write about the “Do” part without also writing about the “Check” and “Act” parts, as they are interconnected. The “Do” part is where you enter the experimental phase. We implement the plan and see if it is working as expected. If it is, then we can move on; but, more than likely, it is going top need some adjustment. It may, in fact, require continuous adjustment.

Hopefully, in the planning stage you matched the program you are going to implement to your particular organization. Yes, you are unique. Just as no two people are the same (even identical twins), no two organizations are the same, either. This is why the “plug and play” idea that is so prevalent lends itself to good programs failing.

Enter the dragon

I use a philosophy that I learned studying martial arts. Not your typical strict study of the ancient form, but the fluid and flexible style of American Kenpo, which has influences from Bruce Lee. Lee was not well received in the martial arts community because he broke from the traditional martial arts form of teaching the precise, exacting style of the ancient art. Don’t get me wrong — Lee taught the ancient forms but believed we are all individuals with individual capabilities and abilities. He taught the traditional styles but didn’t stick with one style because he found that, as individuals, we could do some things better than others and other things not so well.

You mix up the styles; take from here and there and use what works for you. In essence, you don’t learn an ancient martial art but you take from many martial arts styles and create your own style that is unique. As Lee said, “You use what works for you.” You adapt and adopt. When the martial arts style fits with your individual physical dexterity and mental makeup, it is more effective and responsive than if the style were forced upon you and you do not possess the physical or mental ability to perform it to its full capability.

Ed Parker created American Kenpo when he added a science variant to the principles that Lee taught. The science was the study of the various moves in martial arts looking at improving efficiency, reducing wasted motion and increasing fluidity of action. Sounds like a quality system, doesn’t it? Isn’t this what you are seeking in running a business? Use what works for you and adapt it to your style. Look at improving efficiency, reducing waste and increasing fluidity of motion. Adopt it in your life so it becomes the norm and second nature — but be aware that as things around you change, you have to change also. This is how we evolve.

Early quality processes

Just because much of the literature on quality processes is filled with Japanese words doesn’t mean that the Japanese were the inventors of quality processes. These processes came from many sources, America being one of the more prominent ones. After WWII, we sent Deming and Joseph Juran, our best quality experts, to Japan. Actually, after WWII we had no use for those individuals, as we were in a production mode and the public was buying anything that could be produced. Did the Japanese just take everything that Deming and Juran provided and used it? No. They took them and adapted them to their organizations and then adopted it into their culture and they made it their own. They had the patience to let it flourish with continual adjustment.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, a label of “Made in Japan” was synonymous with junk. Japanese autos were unreliable, their electronics were of poor quality and the motorcycles were made of stamped steel and just looked bad (but not the good bad). The Japanese kept at it and made slow, methodical improvements over many years. Then, all of a sudden, the Japanese car is a mark of the highest quality, reliability, resale value and ability to run forever. The electronics are the top of the line and their motorcycle industry almost wiped out the American motorcycle off the map. How did that happen so fast?

Slow and methodical

The American auto industry may have thought of it as a surprise attack, but it was anything but. There is something to be said about slow, methodical improvements; they work. If you really want to know, it is called Kaizen. Do you know how to eat an elephant? One small bite at a time — but over time, if you measure your progress, it is considerable.

I was using a hand posthole digger to dig my window wells of my house. I don’t know if you have ever used one before, but it takes a very small portion of dirt out at a time and you think it will take forever. It is amazing how much dirt I removed in a half an hour. That is the concept.

Another advantage to moving slowly is that the change process can be relatively painless. This doesn’t mean that you ignore opportunities when you see them, but always improve, even if it just minutely. We complain when the gas price goes up five cents, but we appear to tolerate an increase of one cent per month. If gas in 1965 was 50 cents per gallon and it went up one cent per month, it would be more than $5 per gallon today. Big change — but we probably didn’t feel it creep up on us and are only shocked when we look back. This is true of almost everything.

Matters at hand

Getting back on track here, you implemented the plan, you see problems, and you make adjustments. You need to ask what needs to be changed. Does the plan need to be modified, are there unanticipated resources required, are there outside influences that weren’t factored? First off, you can’t do this analysis in a vacuum. Solicit help from your employees.

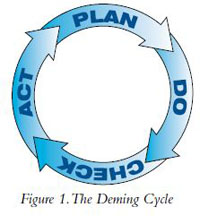

After the adjustments, you check it and ensure it is doing what you wanted. If it is, then you solidify that process. This is the adoption phase and is the “Act” part of the Deming cycle. You have successfully implemented the plan and now you can sit back and relax and let everything run free wheel, not a care in the world. Not so, young one. This is called the Deming Cycle, not the Deming Program. A program has a beginning and an end; this is a cycle, so you start all over again. Actually, you continue the process of continually monitoring, checking and adjusting as necessary.

Deming Cycle

What happened to planning in the cycle? It’s still there. Look at figure 1; it is fed by the act of implementing the plan. As we progress through the cycle, the act of normalizing and institutionalizing the plan doesn’t create an end. What has been created is another area to continually assess to continually improve.

The bottom line is, well …. the bottom line. We are in business to make a profit. The formula to increase profits is simple: increase income and/or decrease cost. Continually improving brings in more business because, as consumers, one thing that attracts us is quality. Continual improvement improves efficiency and decreases cost. The second thing we are attracted to as consumers is value. The “Red Queen” said she had to run faster and faster just to keep up, but if she improved the efficiency of her stride, she could run faster and expend less energy.

The bottom line is, well …. the bottom line. We are in business to make a profit. The formula to increase profits is simple: increase income and/or decrease cost. Continually improving brings in more business because, as consumers, one thing that attracts us is quality. Continual improvement improves efficiency and decreases cost. The second thing we are attracted to as consumers is value. The “Red Queen” said she had to run faster and faster just to keep up, but if she improved the efficiency of her stride, she could run faster and expend less energy.

Patrick Kinane joined the Air Force after high school and has worked in aviation since 1964. Kinane is a certified A&P with Inspection Authorization and also holds an FAA license and commercial pilot certificate with instrument rating. He earned a B.S. in aviation maintenance management, MBA in quantitative methods, M.S. in education and Ph.D. in organizational psychology. The majority of his aviation career has been involved with 121 carriers where he has held positions from aircraft mechanic to director of maintenance. Kinane currently works as Senior Quality Systems Auditor for AAR Corp. and adjunct professor for DeVry University instructing in Organizational Behavior, Total Quality Management (TQM) and Critical Thinking. PlaneQA is his consulting company that specializes in quality and safety system audits and training. Speaking engagements are available with subjects in Critical Thinking, Quality Systems and Organizational Behavior. For more information, visit www.PlaneQA.com.

Patrick Kinane joined the Air Force after high school and has worked in aviation since 1964. Kinane is a certified A&P with Inspection Authorization and also holds an FAA license and commercial pilot certificate with instrument rating. He earned a B.S. in aviation maintenance management, MBA in quantitative methods, M.S. in education and Ph.D. in organizational psychology. The majority of his aviation career has been involved with 121 carriers where he has held positions from aircraft mechanic to director of maintenance. Kinane currently works as Senior Quality Systems Auditor for AAR Corp. and adjunct professor for DeVry University instructing in Organizational Behavior, Total Quality Management (TQM) and Critical Thinking. PlaneQA is his consulting company that specializes in quality and safety system audits and training. Speaking engagements are available with subjects in Critical Thinking, Quality Systems and Organizational Behavior. For more information, visit www.PlaneQA.com.