When Do We Do Root Cause Analysis?

Root cause analysis is a hot topic and it is closely connected with the infamous “dirty dozen.” However, is 12 too large a number for management to grasp? Many think it is, otherwise we wouldn’t have the proliferation of seven being the optimal number. We have “seven habits of effective people” (is this all they could muster up?), “seven wonders of the ancient world” (I’m sure there were more wonders than that), “seven deadly sins” (I guess the other sins you could live through) and “the 10 commandments” (oops, that one slipped by, but it looks like it is a keeper.) The dirty dozen has been under attack to pare it down as well, probably due to conversations such as the following between management and supervision. This is a one-sided conversation, but you can determine what the other party is saying easy enough.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER: The following conversation is fictional and any resemblance to a real conversation past, present or future is purely accidental. (Hint, hint, wink, wink!)

“How come Joe smacked his head on the antenna?”

“So what if he worked over 10 hours, he got paid didn’t he?”

“OK, I’ll ask again, how come Joe smacked his head on the antenna?”

“Alright, I’ll give in since you insist; wait, let me pull out the list. Let’s see, yes, it’s fatigue, right out of the dirty dozen list. Great! Put a fork in fatigue and let’s call this root cause done. How’s the antenna?”

“It’s what? There’s what? More.”

“No, that’s impossible. You can’t have fatigue and distraction. This is called root cause analysis, not root causes. You can only have one. Those are the rules.”

“We labeled it fatigue — that’s it, we are done, finished, finito, don’t make this more complicated than it already is. Our job here is finished so let’s move on. The root cause has been identified. Joe was fatigued, so give him three days off without pay so he learns his lesson to get sleep. We give him 12 hours to himself and if he doesn’t sleep during that time, it is his fault”

“What do you mean he was distracted also? That’s because he should have slept, he was probably day dreaming and not paying attention on top of it.”

“What? That reminds you of another thing? Awareness ... are you serious? That’s impossible.”

“This is getting ridiculous. Do I have fire both Joe and you?”

“Another one.”

“What?! Pressure? I’ll give you pressure! You and Joe can both get three days off without pay.”

“What do you mean ‘two more on the dirty dozen list?’ Pressure is only one more. You’re really starting to frost me.”

“Pressure and stress? That’s it — you’re fired ... and take your friend Joe with you.”

Private thoughts: “Now that they are out of the way, let me write this down — fatigue is the cause and that’s it. Joe is terminated for negligence and damage to company property and his unreasonable supervisor for insubordination and willfully not following company policy, namely human factors. Since they are no longer with us, the problem is gone and the solution is complete. I’ll be the hero to upper management when they see that I took a firm stance against those who oppose human factors. Upper management likes human factors. I’ll be the root cause king for getting this done quickly. Now let’s see if I can get the rest of these clowns to cooperate and do some work.”

Root cause analysis can take many forms and organizations have to find a methodology that fits. Root cause is designed to find the origins of problems so you can implement effective solutions directed at the cause and not the symptom. That sounds simple enough, right? There is one major airline that had begun a robust proven root cause analysis process. However, the root cause is conducted after disciplinary action. Yes, you read that correctly — after disciplinary action. They conform to the construct that you arrest someone for murder, hang them, and then have a trial. That is perfectly normal for this airline as it fits into the ready-shoot-aim managerial theme that it has adopted. The airline management is also bewildered by a lack of mutual management-employee trust. Go figure.

Addressing the problems

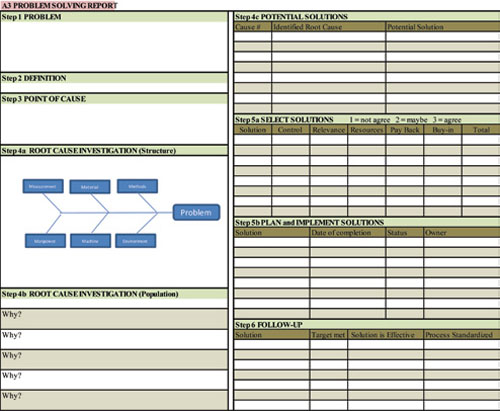

There are numerous horror stories about human factors and root cause analysis. Addressing problems requires four main issues: identification, containment, resolution and monitoring. As previously stated, there are many methods available. The one I’m going to introduce isn’t “find me a victim.”

It all begins with questions. Inquisitiveness and curiosity are your friends. What I am getting at is that there are a lot of questions to ask to determine if the obvious is the problem or if the cause is deeper. If you skip this analysis stage and fixate on the obvious, you may continue to have similar issues in which case you have not dug deep enough into root cause. You will have only corrected a symptom. Some organizations are stuck in this mode and wonder why they have the same recurrent problem. Conversely, accomplishing a root cause analysis (as depicted here) on every issue is time consuming and not cost beneficial.

If the analysis is done properly, you could end up with a number of causes and an equal number of viable potential solutions. Your next step is to prioritize them to see which will give you the biggest bang for the buck. The buck and bang are measured by your ability to control the implementation of the solution, the relevance of the solution to the problem, availability of resources, what the payback for the solution (cost/benefit) is, and if there is buy in from those involved or going to be involved.

From this prioritization task you can assign each solution to an individual (the owner) and provide them with the necessary resources to be successful. The last step in the root cause analysis is the follow up. This isn’t intended to see if the owner is completing the task, rather to determine if resources are adequate and if the solution is both progressing as planned and maintainable.

This is simply the formalized format of what we do intuitively. If we walk into our house and the carpet is wet, the first thing we do is identify the reason. A pipe burst. The next thing we do is shut off the water supply to the pipe to contain the leak and keep it from spreading. Then we start to analyze what happened to determine a solution. Why did the pipe burst? Was it hit by something, is it corroded, was a faulty pipe, etc.? Is this an isolated incident or systemic? Could other pipes be ready to burst? Does the pipe need to be replaced or should a plumber be called to evaluate the system? We formulate a repair, implement the repair, then follow-up to ensure that the repair is completed as planned.

Not all problems need to go through this process as it’s based on our exposure to risk, repeatability and severity. If the tires on our car have 60,000 miles and are worn, we replace the tires. No need to go into a deep analysis into a root cause — but if our tires were worn at an abnormally low mileage, we may want to determine why. We might have a frequency issue. If one tire is worn more than the others, we concentrate on the worn tire which is a criticality issue. What about hidden damage? Certain tire brands might be susceptible to internal damage so we would have a detectability risk issue.

Probability Statements

We also don’t need to have a problem to use this process. With a little adjustment, this process lends itself well to improvement projects and predictability by adding probability to the equation. Instead of looking into how often an issue occurs, how serious it is when it does occur, and how easily it’s revealed when it occurs, we turn those questions into a probability statement. We have a higher likelihood that our tires will be worn with 60,000 miles as opposed to 10,000 miles. The chance of one tire wearing more than the others is dependent on a number of associated events, alignment, road conditions, etc. If we keep our car aligned, our chances of one tire wearing more is less than if we don’t. The possibility of having internal problems may be higher with an off-the-wall brand tire than a name brand.

Risk priority numbers

Let’s say we rank each component: repeatability (R), severity (S), and detectability (D) on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the worst. The product of R, S and D will result in a risk priority number (RPN). This would help in determining if we need to enter into a formal root cause analysis. We set the criteria threshold. Let’s say we want to analyze anything with a RPN over 5, so in Figure 1, issue No. 3 would get full root cause analysis treatment followed by No. 2. No. 1 would not require analysis. There is a logical prioritization construct to resolve ties. If two analyses have the same RPN, the one with the highest severity should take priority because it deals with the effect of the failure. This is followed by detectability over repeatability, as it may affect the customer. We define the parameters on what our organization feels is critical.

The RPN chart can also be used to measure progress. After we have completed the application of the root cause analysis solution, incorporate the same measures of the results as we used before to determine if the RPN has improved. Is the RPN lower? Did we fix the problem, or improve the issue, and by how much? The RPN chart can be used for much more but space is limited.

Some of you will recognize the analysis as a modified version of the A3 root cause analysis process, Figure 2, with a hint of failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA). The A3 is a standardized collection of common quality tools that was formalized by Toyota. I know, Toyota has taken some pretty hard hits lately, but their cars are still rated as the most reliable on the market. Their penchant for reliability is due to a number of processes and the A3 is just one of them.

Refreshers and reminders

It appears that we lost human factors along the way. Not really, as it will be unveiled during the analysis process. And yes, my friend, there can be more than one root cause and multiple solutions. Remember the Swiss cheese figure we were introduced to in human factors training? The fact that we have plugged one hole doesn’t measure robustness of our solution — we have just created a weak link. If that weak link is our containment action, we have more roads to tread before we get home.

To answer the topic question of when you do root cause analysis — always. However, the depth of the root cause analysis must be commensurate with the risk level of the issue.

Patrick Kinane joined the Air Force after high school and has worked in aviation since 1964. Kinane is a certified A&P with Inspection Authorization and also holds an FAA license and commercial pilot certificate with instrument rating. He earned a B.S. in aviation maintenance management, MBA in quantitative methods, M.S. in education and Ph.D. in organizational psychology. The majority of his aviation career has been involved with 121 carriers where he has held positions from aircraft mechanic to director of maintenance. Kinane currently works as Senior Quality Systems Auditor for AAR Corp. and adjunct professor for DeVry University instructing in Organizational Behavior, Total Quality Management (TQM) and Critical Thinking. PlaneQA is his consulting company that specializes in quality and safety system audits and training. Speaking engagements are available with subjects in Critical Thinking, Quality Systems and Organizational Behavior. For more information, visit www.PlaneQA.com.

Patrick Kinane joined the Air Force after high school and has worked in aviation since 1964. Kinane is a certified A&P with Inspection Authorization and also holds an FAA license and commercial pilot certificate with instrument rating. He earned a B.S. in aviation maintenance management, MBA in quantitative methods, M.S. in education and Ph.D. in organizational psychology. The majority of his aviation career has been involved with 121 carriers where he has held positions from aircraft mechanic to director of maintenance. Kinane currently works as Senior Quality Systems Auditor for AAR Corp. and adjunct professor for DeVry University instructing in Organizational Behavior, Total Quality Management (TQM) and Critical Thinking. PlaneQA is his consulting company that specializes in quality and safety system audits and training. Speaking engagements are available with subjects in Critical Thinking, Quality Systems and Organizational Behavior. For more information, visit www.PlaneQA.com.