The Characteristics of...

A&P

Airframe & Powerplant

AMT

Aircraft Maintenance Technician

AME

Aircraft Maintenance Engineer

LAME

Licensed Aircraft Maintenance Engineer

All OF WHOM MAINTAIN AIRCRAFT

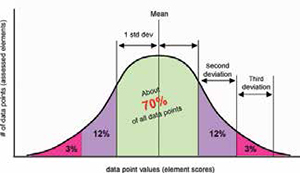

Before anyone says that I am stereotyping or — worse yet — profiling, let me introduce you to the Bell curve.

The Bell curve is a grading tool that is often used to help ensure that an entire class does not fail or pass.

In 1992, Giselle Richardson compiled a list of 10 personality characteristics of those who work in aircraft maintenance. What the Bell curve tells us is that about 50 percent of us will have about 70 percent of the characteristics.

A few will have none of the characteristics and about the same number will have all of them.

Let’s see where you fit in and look at the good, the not-so good and the downright ugly. Tick off the ones that might apply to you.

1. Have a high degree of dependability. We are a dependable lot. We trust that the newcomers will learn from the old-timers that when an aircraft is down for inspection or repair, a lot of people are depending on them to be there and to do it right.

2. Have a willingness to put in effort and hours. The majority of maintainers I know need to demonstrate this trait all too often. When an aircraft has to get out by a certain time, they are there. Some of them might be grumbling, but they are there.

3. Have a high level of integrity. A high percentage of us will fit into this category. Even when an error is made, it is usually with the best of intentions.

4. Have a high level of modesty. Some of us have too high a level, but we are improving. If you recall a couple of articles back, Richardson said we had too much “humbleshit.” Back in those days, there were no magazines such as this one devoted to you and you never saw a maintainer on the cover page. Yes, we are improving.

5. Have a distrust of words. Now that is an interesting trait that was explained to me, as we tend to want to find out for ourselves when we read a snag written in a log book. That’s not all bad, as I can recall a pilot writing up that the left magneto on the right engine was misfiring. I would run the aircraft up before trouble shooting only at times to find out that the problem was on the left engine’s right mag — and the problem was a fouled sparkplug, not the magneto.

6. Tendency to be a loner. Richardson didn’t say that we were loners but we tend to have some of the characteristics, such as:

a) prefer to work alone;

b) tend to be perfectionists;

c) are often not the best team players; but,

d) we tend to be very analytical and principled.

Some are strengths and some we should work on improving.

7. Don’t like to ask for help. I remember an AME up on a scissor lift, struggling to secure the bottom cowl on the No. 1 JT8D engine on a Boeing 727. Under the lift were two of his crew, discussing last night’s hockey game. (This was Canada, after all.) I’m sure that if he had asked, they would have climbed up and assisted. As he struggled, his feet would come within inches of the unprotected edge of the lift. After watching for a while, I walked on. After all, who was I to interfere with a job he obviously wanted to do himself?

8. Tends to be self-sufficient. This refers back to the previous two and is not entirely a bad thing. However, like so many things, if taken too far it can endanger lives — often the life of the person doing the act. Had the self-sufficient person stepped back a few inches more, he would have been in a world of hurt after a 10-foot fall to the concrete from the lift. As we didn’t wear hard hats in those days, he could have been killed and we would have been short one in the crew for a while. Health and Safety have improved immensely over the years, but we still tend to have the same self-sufficient attitudes.

9. Like to think things out on his/her own. Urban legend says that men don’t like to ask for directions (except from that woman’s voice in my GPS), so Richardson is probably right. This trait can be dangerous when one is not sure just how a fitting goes in, but it looks like it should go THIS way. Murphy’s law dictates that we will be wrong. I replaced a leaking vacuum flap control valve in a Grumman Goose on a midnight shift and couldn’t get the aircraft outside to test run it. I signed it out subject to a satisfactory test run. The next morning, the pilots ignored that and loaded some high-priced passengers on board. Thank goodness there was nothing under the flaps as they went full down on engine startup. A rush call got me out of bed to reverse the valve and paint an arrow on it as well as do a ground check before signing it off. I guess I get a tick mark for that one.

10. Doesn’t share his/her thoughts frequently. I was conducting a class in Winnipeg when an out-of-town participant asked if his wife could sit in the back and do her knitting so she would not go out shopping. Well, I could relate well to that so I did one better and put her in one of the teams, far removed from her husband. She was certainly not lacking in assertiveness and soon was leading her team, even if she had never turned a wrench in her life. When this characteristic came up, she said in a very loud voice, “Yes, that’s right! He never tells me anything!” He tried to quiet Mabel down but she went on. “He comes home and I ask him how his day went and all I ever get is ,‘OK.’ What is that supposed to mean?” He weakly responded, “But you wouldn’t understand,” to which she replied, “Try me.” As the class was quickly turning into a marriage counseling session, we took a short break. He certainly gets a tick mark for that trait.

I’d like to add a few more that I have observed over my 54 years in aviation.

11. We are mechanically or electronically inclined, but very seldom both.

12. We have a strong “can-do” attitude. That is an excellent attitude but it can get us into trouble if we have trouble saying no or admitting that we might need help (see No. 7).

13. We are pore spelers. This mug that Richardson gave me says it all. This was after I introduced her in a symposium program as, “a much-sought-after pubic speaker.”Spell check failed me and she said that it was the best lead-in she had ever had. For those who didn’t spot the error, I meant to say “public speaker.”

My article in the next issue will take us back to Lack of Communication but will focus on the written word.

We’ll look at an accident in which 24 lives could have been saved if a log book entry had only been written correctly. OK — there were a lot of extra links in the chain of events but that one could have made the difference and broken the chain.

We are professionals and have to do more to show it. Look at the image of the blue poster that we have in stock that lists 10 reasons why I think you are a professional. Sadly, No. 7 is where we are the weakest. If you go back over this list you will understand why. We can do better and must if we are going to lower maintenance errors to as low as reasonably practical (ALARP). I don’t believe that zero error is possible as we humans are genius at finding ways to get around Safety nets devised to prevent human error. That said, we can still strive for the impossible dream.

Gordon Dupont worked as a special programs coordinator for Transport Canada from March 1993 to August 1999. He was responsible for coordinating with the aviation industry in the development of programs that would serve to reduce maintenance error. He assisted in the development of Human Performance in Maintenance (HPIM) Parts 1 and 2. The “Dirty Dozen” maintenance Safety posters were an outcome of HPIM Part 1.

Gordon Dupont worked as a special programs coordinator for Transport Canada from March 1993 to August 1999. He was responsible for coordinating with the aviation industry in the development of programs that would serve to reduce maintenance error. He assisted in the development of Human Performance in Maintenance (HPIM) Parts 1 and 2. The “Dirty Dozen” maintenance Safety posters were an outcome of HPIM Part 1.

Prior to working for Transport, Dupont worked for seven years as a technical investigator for the Canadian Aviation Safety Board (later to become the Canadian Transportation Safety Board). He saw firsthand the tragic results of maintenance and human error.

Dupont has been an aircraft maintenance engineer and commercial pilot in Canada, the United States and Australia. He is the past president and founding member of the Pacific Aircraft Maintenance Engineers Association. He is a founding member and a board member of the Maintenance And Ramp Safety Society (MARSS).

Dupont, who is often called “The Father of the Dirty Dozen,” has provided human factors training around the world. He retired from Transport Canada in 1999 and is now a private consultant. He is interested in any work that will serve to make our industry safer. Visit www.system-Safety.comfor more information.